Crafting the unwanted into family heirlooms

Published 12:53 pm Thursday, January 13, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

BY IVAN SANDERS

STAR STAFF

ivan.sanders@elizabethton.com

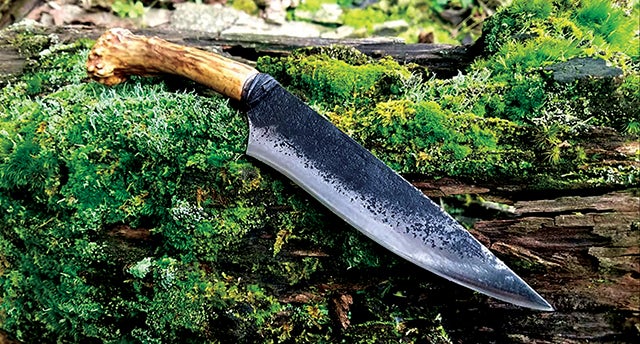

A spray of hot metal chips flies behind the grinder as Alex Campbell works to create the perfect edge on a new knife he has been creating for a couple of days. Four more blades are in different stages of being ready for the finishing touches of grinding and sanding.

To date, Campbell has completed 300 in his five years of knife making.

So how did an educator in the Elizabethton School System learn to turn raw steel and deer antler into knives that can be passed down for generations to come? It was a deep love of history and wanting to participate in the frontier day activities at Sycamore Shoals State Park.

“I love going down to Sycamore Shoals and watching those re-enactments,” Campbell said. “They have weapons, clothes, and tools like they did a hundred years ago. And I wanted to do that. I thought it would be cool to do that. I could go and help other people learn history. I started talking to them and they told me I had to get the clothes, gun, and bag and other stuff.

“I was like, ‘how much do those things cost?’ They were all hand made because in the day they were all hand made. You can’t go to Walmart and get this stuff. You have to make it by hand or buy it from someone who had made it by hand. I asked how much one of those guns would cost and they said $3,500. I asked about the knives and they said $300. The shoes were $200. I thought I couldn’t afford it. That’s when I thought that I would try to make it myself.”

Campbell put out a call to his hunting buddies and told them that if they killed a deer to bring the deer hide to him so he could try tanning it to make something out of it.

The call was returned by Jay Scurry, another teacher at Elizabethton High School.

“Jay told me he had rolled into school with a deer in the back of his truck,” Campbell said. “I stuffed that deer hide into a mini-fridge that I cleaned out in my room. During my planning period, I got online and looked up how to tan a deer hide. When I got home, I tanned it and it didn’t turn out well. It was hard and stiff and it made me mad.

“I had to get another one and then another and another and finally I eventually got to where I could decently tan a deer hide. Those first ones were so tough that you could make a suit of armor and not a shirt out of them. So, I started to think what I could do with a tough deer hide. I thought that I could make a knife sheath and I didn’t even have a knife.”

Campbell had 10 deer hides in his outbuilding and realized he needed to do something with them. He decided to start making bags, knife sheaths, and other items.

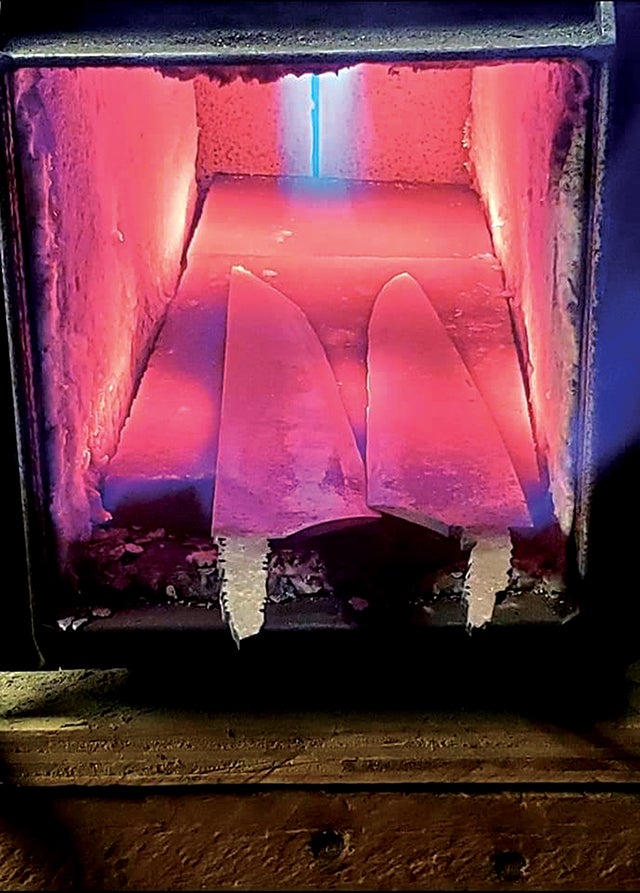

But the yearning to make knives still burned deep, and he knew he needed a forge to heat the metal. He was given a one-brick forge that could only forge a six-inch piece of metal. He soon discovered that to create a longer blade, the metal could be flipped around to forge the other end.

Pretty soon, Campbell had mastered the art.

“Getting a good edge profile on it” is the most critical part, Campbell said. “It has to be smooth and has to be one angle. If you have a lot of money you can go buy a machine that has a ‘jig’ in it that holds the blade at the exact angle and you just turn on a grinder and it will sand it perfectly. I hold it by hand and eyeball it and try not to sand my finger off. To get a really good blade profile makes it cut really good.”

And while there are varying opinions on what type of metal makes the best knives, Campbell has his own favorite.

Campbell searches for the large old circular sawmill blades from a hundred years ago which he says have amazing steel in them. He will spend $100 for one of the blades, bringing it home to cut and forge. And to expedite the number of blades he can forge, he recently purchased a two-burner forge.

“You do not make one knife from beginning to end; that would take forever,” Campbell said. “It has to lay in the forge for a few minutes to get hot, so I usually have something else that I am working on. Right now, I have five knives going at the same time.

“While one is in the forge, I have something else going on over here. And while I temper that one, I am doing something over here. It usually takes three days to finish a knife. There might be two to three knives. I am not working eight hours a day on just one knife.”

He said one of the most challenging custom knives he tackled was for a customer who wanted a three-part handle with antler, some type of metal, and then a horn, and wanted aN S-shaped guard made of Damascus and a blade made of Damascus.

Damascus steel was forged steel in the blades of swords smithed in the Near East from ingots of Wootz steel either imported from Southern India or made in production centers in Sri Lanka, or Khorasan, Iran.

Besides making knives, Campbell also has learned the craft of making powder horns intended to keep gun powder dry.

“Powder horns are the hardest thing to make,” Campbell said. “Basically you take this hard thing that was on a cow’s head and turn it into something awesome. You cut the horn off and there are two ways to get the stuff out of the interior of the horn. You can either bury it or boil it out.

“Boiling it you can do in a few minutes but it stinks. Burying it takes six months but it doesn’t stink. You have to sand forever to get it where it’s smooth. You have to make it air tight as well so I do a two-part stopper. I put a piece of wood that fits perfectly over the horn opening and then I put another piece on top of it called the cap.”

What makes the powder horn so delicate is the process it takes to put a design on the outside. The process might take a week just to put the scratches on it and then ink has to be filled into the scratches. From start to finish it takes weeks and weeks to get the powder horn ready to be sold.

Campbell uses the summer months to focus on the powder horns due to the time constraints of making them. He said it has also become harder and harder to find American cattle with white horns.

Campbell sells his products through Laurel Fork Primitives and has shipped to customers in China, Germany, Finland, Portugal and Canada.

While history pulled him into the art, being able to craft custom pieces for customers has kept Campbell engaged. Customers, such as the person who brought the antlers of a buck killed by his late grandfather, inspire Campbell, who turned those antlers into knives for the family heirlooms.

When all is said and done, Campbell said it was not about the number of knives, powder horns, bags, or shoes made; it’s about knowing that you have been able to take something that many thought was worthless and nothing more than waste and turn it into something that can be appreciated for years to come.