The bloody era when Tennessee became a state

Published 8:00 am Wednesday, November 30, 2022

1 of 2

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Bill Carey

This is about the time of year that fifth and eighth grade teachers do a lesson on how Tennessee became a state. If they aren’t careful, this lesson might be boring, and the events might seem inevitable.

But that era was anything but boring.

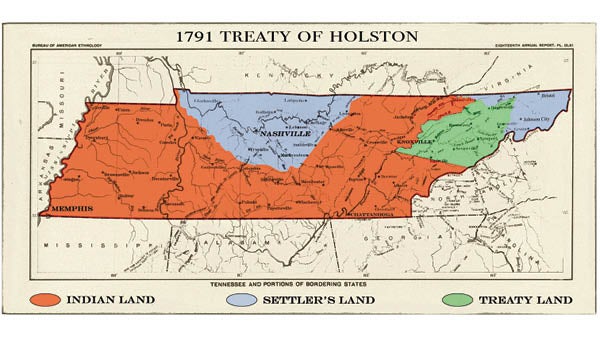

From 1790 until 1796, present-day Tennessee was known as the Southwest Territory, and about five-sixths of it was owned by Native American tribes. The Cherokee Nation still owned and controlled all of present-day East Tennessee south and east of Kingston, the Cumberland Plateau, and most parts of Middle Tennessee drained by the Tennessee River. The Chickasaw Nation owned all of present-day West Tennessee.

As far as white settlers were concerned, Tennessee consisted of two separate pieces of land divided by the “vast wilderness” of the Cumberland Plateau.

Under the terms of the Treaty of the Holston, settlers were supposed to have unlimited access to a road that connected the two areas and crossed the plateau. But there were so many acts of violence along the road that most people only travelled it with military escort. Every few months, those military escorts left Fort Southwest Point (in present-day Roane County) heading west and Fort Blount (present-day Jackson County) heading east.

“On the 20th of October next,” reported several issues of the Gazette in the summer of 1795, “the annual escort through the wilderness for families will leave the blockhouses at Southwest point for Bledsoe’s Lick [in Sumner County].”

The Knoxville Gazette, Tennessee’s only newspaper at this time, was full of stories of violence between settlers and Native Americans. The January 9, 1795, Gazette reported three deaths on the Harpeth River, west of Nashville. The February 6, 1795, issue contained a tidbit about the death of George Man, who lived in present-day Sevier County. On March 27, 1795, the Gazette reported two deaths at Joslin’s Station near Nashville.

The May 8, 1795, issue reported several acts of violence, including the death of a soldier “on duty at the Fort of Cumberland” (near Fort Blount). That same issue of the paper reported that a planned prisoner exchange between the United States government and the Cherokee Nation was “postponed to a future day.”

The Gazette occasionally reminded readers why Native Americans were fighting in the first place. On January 8, 1795, Southwest Territory governor William Blount issued a formal proclamation ordering all settlers who had illegally moved into the area known as Powell’s Valley to leave immediately and “to warn them that in case of a refusal to neglect to obey this command, that they will answer the same at their peril.”

What did this search through early issues of the Knoxville Gazette lead me to conclude?

One is that it is misleading to use a current map of Tennessee when you talk about Tennessee becoming a state. After all, the vast majority of present-day Tennessee was Native American land when Tennessee became a state.

The other point that needs to be emphasized is why Tennessee’s early inhabitants were so anxious to become a state in the first place. When Tennessee became a state, its leaders were hopeful that the federal government would do more to help its residents fight. (That, by way, is why the government of the Southwest Territory had renamed White’s Fort after Secretary of War Henry Knox back in 1791.)

Somehow the residents of the Southwest Territory survived. In 1795, a census showed that the Territory South of the Ohio River had about 60,000 residents, more than the minimum requirement set by Congress. The next year, eligible voters chose to become a state by a margin of three to one. Delegates were elected to write a state constitution and to come up with a name for the state.

Delegates voted to name the state “Tennessee.”

The constitution was a lot like the one that the nation had just adopted. It called for three branches of government: an executive branch led by a governor, a judicial branch led by a state supreme court and a legislative branch consisting of a house and a senate.

Congress, meeting in Philadelphia at the time, approved statehood on June 1, 1796.

To see a Tennessee History for Kids “KidsINAR” on this subject, go to www.tnhistoryforkids.org, click on the box on the left and scroll down to “Tennessee’s Bloody Road to Statehood.”