Civil War medicine could yield a deadly cure

Published 10:40 am Monday, August 4, 2014

A simple cut or stomach distress isn’t usually enough to send people to the doctor today.

But for a soldier during the Civil War, those conditions could be much more serious – serious enough to send him to the undertaker.

For a while Friday afternoon, the annual Civil War Camp at the Carter Mansion strayed from cannon and bayonets to look at common medical conditions, medical tools, medicines and treatments during the Civil War.

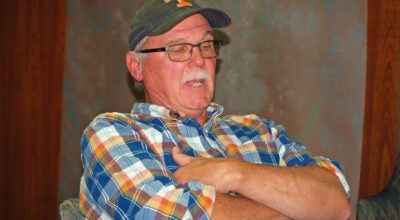

Sycamore Shoals State Park Interpretive Ranger Chad Bogart and other reenactors and interpreters took visitors back in time to look at how certain illnesses and battlefield wounds were handled in the 1800s.

Reenactor J.C. Davis told camp attendees that many conditions that are overcome today – think measles, diarrhea and simple cuts – would often be deadly for Civil War soldiers.

“It all traces back to camp life,” Davis said. “Camps were filthy and they didn’t take the health precautions that we take today.”

Often, soldiers would not boil or purify their drinking water. Davis said they would drink directly from streams or springs and would sometimes share their water supply with their horses.

Also, soldiers did not frequently bathe, sometimes going as many as six months between baths. While latrines were dug away from camps to be more sanitary, Davis said many soldiers would not make the walk to the bathroom facilities and would relieve themselves in the same area where they lived, ate and slept.

Bogart said this was likely because people were not yet aware that germs existed. Scientists had not yet discovered germs, so individuals were not aware that safety precautions needed to be met to stay as healthy as possible.

Not all injuries and illnesses came from everyday life. Some were inflicted on the battlefield.

Bogart said for soldiers receiving minor wounds, lead poisoning was a real concern if the rifle Minié ball was left inside their body. For those shot in the abdomen, death was extremely likely, and those with severe gunshot wounds in an arm or a leg could expect an amputation, which 80 percent of the time also led to death.

“Compared to modern weaponry, the bullets traveled slower,” Bogart said. “They were designed to leave a small hole when entering, and if they exited at all, they would leave a larger hole. When someone was shot, the bullet would get in there and bounce around and do a lot of damage. If someone was shot in the abdomen, more than likely they would die. If they survived the shot, then it was likely an infection would get them.”

Soldiers who survived the initial shot would be taken to a battlefield surgeon. Surgeons would treat soldiers from both sides, but would tend to the soldiers from their side before treating the enemy fighters.

Bogart said when a surgeon saw someone had been shot in the arm or leg, the doctor would probe the wound, either with a metal rod or their finger, to see if the bullet could be removed. If the bullet could be removed, it was retrieved with a bullet extractor that was very similar to a screw driver or by the doctor’s fingers.

If the shot was severe enough to shatter the bone in the extremity, then the arm or leg would be amputated.

Bogart said during this procedure, and all procedures, no pain medicine was given to the wounded individual. The soldier would be given a lead bullet to bite on with the hope they would lose consciousness during the procedure.

To amputate a arm or leg, the doctor would first use a large knife to cut through the flesh to the bone. The assistant would then use cloth or leather to push the flesh up and away from the bone, which would then be sawn in two.

“Some surgeons would have races to see who could amputate the fastest,” Bogart said, noting that it took between 30 and 45 seconds to remove an arm or leg.

After the part was removed, the blood vessels would be tied off and the tourniquet removed. The flesh would then be sewn over the stump and a wool sock would be placed on the end so the stump would heal rounded instead of pointed.

Tooth extraction was not much more pleasant than medical procedures.

If a soldier broke a tooth and needed it removed, hoof trimmers would be used to shatter the tooth to smaller pieces that could be taken out.

The doctor would pick out the larger pieces by hand and then use a metal pin-style probe to pick the smaller pieces out of the gum.

Far too often, the wounds were too severe and the patient died. For some soldiers, this meant a trip to the embalming tent.

Bogart said not every soldier was embalmed: it was a service that families had to pay extra for. Most often it was the officers who were embalmed instead of the enlisted men. The embalming was not completed by an actual doctor but by private businesses who would set up in the camps.

“Imagine how morbid that was for the soldiers,” Bogart said. “These entrepreneurs would set up their tent in the camp and these soldiers would have to walk past it knowing that in a matter of hours they could be sent there.”

The cost to be embalmed was $35 for enlisted men and $85 for officers. Bogart said the difference came from knowing the officers could pay more.

“A body is a body, but they knew who had the money,” he said. “That was a lot of money during the Civil War.”

The Civil War Camp continues Saturday from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. at the Carter Mansion.