East Tennessee History: Harry Burn

Published 11:40 am Monday, August 31, 2020

1 of 1

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

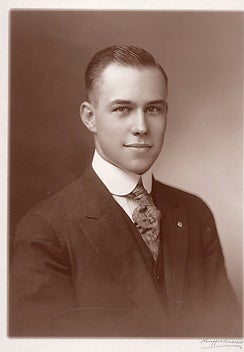

I can image that Tennessee State Representative Harry Burn was nervous on the morning of August 18, 1920. He was just 24 years old, but he had watched as a movement had engulfed the United States. Women all around the country were taking to the streets demanding the right to vote, and today would be his turn to voice an opinion on the subject.

He wasn’t quite sure what he should do about the matter. He had listened to some of the women in his family, including his own mother who said it was just the right thing to do. Others said that running of a country should be left up to men because that is the way it had always been.

These men argued that women were not even allowed to own property in some states until a few decades earlier. Some Southern states even asked what was next? Would black women also want to vote?

Harry Burn had a lot on his mind. The Suffrage Movement had been building for decades. Part of him thought the right for every woman to vote was only fair because women were equal to men. But another part of him considered the change. Women could run for office. Women could have more control in the marriage. There were endless possibilities opening up to the women of America if this amendment was ratified.

With the help of President Woodrow Wilson and hundreds of women who dedicated their lives to the Suffrage Movement, the 19th Amendment had been approved in the United States Congress. The amendment had been voted down six times here, but the seventh vote ratified it and sent it to the states to be ratified.

State after state ratified the amendment until it finally came to Tennessee. Tennessee would be the last state needed to make this law and put the amendment in the books as the 19th Amendment.

In March 1920, the Tennessee Senate and House of Representatives took up the question.

After a political battle that would make the Battle of Gettysburg look like a picnic, the Tennessee State Senate passed the amendment. The story would be different in the House of Representatives.

The vote to pass this amendment failed twice in the House of Representatives with a vote of 48-48 each time. Both times Harry Burn had voted against the amendment because he was being pressured by his own party and the people in his district to hold the line and stop this amendment.

Now, Harry was about to vote again, and he did not know what to do. Should he give women a right that had been denied to them for over 140 years, or should he listen to the people who had put him in office? Should he vote yes because it was the right thing to do or should he listen to the members of his own party and vote this amendment down one more time?

Finally, the vote came, and it was close with a vote of 48-47, in favor of the amendment, but there was one more piece of drama left for this vote. Harry Burn had not voted yet.

If Harry Burn voted for the amendment, it would be ratified and women would have the right to vote. If he voted against the amendment, it would be a tie again and the amendment would fail in Tennessee.

Before he voted, Representative Burn pulled out a piece of paper his mother, Febb Ensminger Burn, had given to him earlier that morning. As he read the words, he knew what he had to do.

The note read, in part, “Harrah and vote for Suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt…I’ve been watching to see how you stood but have not seen anything yet…Don’t forget to be a good boy.”

Burn decided to change his vote on the third vote. Thanks to his single vote, the House approved the amendment, Tennessee ratified it, and the Constitution was changed to guarantee women the right to vote.

Harry Burn’s vote came 100 years ago last week, and it will go down as one of those moments that one person can make a difference. It all happened because one young man decided to be a “good boy” for his mother.