Hampton man was USS Johnston casualty

Published 12:32 pm Friday, May 28, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In April of this year a U.S. Navy destroyer sunk more than 76 years ago was found in “the deepest wreck dive in history.”

The USS Johnston, led by Captain Ernest Evans, sunk in October 1944 after charging “outgunned and outmanned” to protect an American landing force in the Philippines from a massive line of Japanese warships during the Battle of Leyete Gulf, according to Naval History and Heritage Command records

The World War II battle eventually led to American victory, but only after more than 2,600 casualties on both sides. Nearly 190 crew members of the Johnston’s 327 died – including Evans, the first Native American in the Navy to be awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor.

A Carter Countian, Clarence Carden was on the USS Johnston that fatal day and lost his life also. Carden was the son of Mr. and Mrs. Daniel Stover Carden of Hampton, and was one of three brothers to serve during World War II. Brother Bill also served in the US Navy, and Bob served in the US Army. Both came home from the war and resumed their lives. A third brother, Carl signed up for military duty, but was turned down for medical reasons. He ended up on the west coast building Navy destroyer ships.

Clarence died October 24, 1955, in the aftermath of the Battle off Samar and is buried in the Hall Cemetery at Hampton. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

In a letter sent to Carden’s family by a surviving senior officer on the USS Johnston., The officer wrote: “The Johnston was under attack by a vastly superior force of Japanese battleships, cruisers, and destroyers. She fought valiantly for three hours, inflicting heavy damage upon the enemy before we were finally forced to abandon ship.

“Clarence was on the gun crew of one of our main battery guns during the battle. His gun continued to fire, inflicting great damage on the enemy until we were finally forced to abandon ship. While abandoning ship your son was wounded, but assisted onto a life raft where he was given first aid and morphine to ease his pain. Only by his exceptional courage and strength was Clarence able to survive the fifty hours adrift on the life raft. After being rescued he was given medical treatment aboard the rescue vessel but the shock and exposure were too much and he died shortly thereafter. His remains were buried in grave No. 21, United States Armed Forces Cemetery, Leyete, Philippine Islands (his remains were later shipped home for burial).

The officer continued to write: “Your son was a fine man and shipmate and a good sailor. He was admired by his fellow sailors for his good fellowship and courage, and he was regarded by the ship’s officers as a man who could always be relied on in the performance of his duty.”

A Navy newsletter related the sinking of the USS Johnston during the Battle of Samar, which was part of the larger, sprawling Battle of Leyete Gulf.

With the outcome of the war already decided, the Japanese were seeking little more than a ‘‘fitting place to die,” according to planning documents.

Despite technological superiority, American hubris, largely that to Admiral Bill Halsey, led unsuspecting US sailors into the hands of a much larger Japanese force comprised of four battleships – including super battleship Yamato – six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and 11 destroyers.

Led by Commander Ernest Evans, the heavily outmatched destroyer “charged into a massive line of Japanese warships in order to protect the American landing force attempting to liberate the Philippine Islands,” the NHHC wrote.

The move reflected Evans’ assertion on the day of the Johnston’s commissioning, when he declared, “This is going to be a fighting ship. I intend to go in harm’s way, and anyone who doesn’t want to go along had better get off right now.”

Enemy shells assailed the onrushing Johnston, striking the destroyer and inflicting widespread damage and casualties. Despite being seriously wounded in the attack, Evans ordered a second assault.

With no remaining torpedoes and limited firepower left, Johnston’s brave but doomed attack continued unabated, firing 30 more rounds into a 30,000-ton Japanese battleship.

As enemy ships began strafing the escort carrier Gambier Bay, Evans gave the order to “commence firing on that cruiser, draw her fire on us and away from Gambier Bay.” The Japanese responded in turn.

“After two-and-a-half hours, Johnston — dead in the water — was surrounded by enemy ships,” the Naval History Center release said. “At 9:45 a.m., Evans gave the order to abandon ship. Twenty-five minutes later, the destroyer rolled over and began to sink.”

Of the 327-man crew, only 141 survived. Evans was not among them. The commander was later awarded the Medal of Honor, becoming the first Native American in the U.S. Navy and one of two destroyer captains in WWII to receive the honor.

“In no engagement in its entire history has the United States Navy shown more gallantry, guts and gumption than in the two morning hours between 0730 and 0930 off Samar,” Rear Adm. Samuel Eliot Morison wrote.

Because of Evans’ bravery and Johnston’s sacrifice in diverting Japanese attention, General Douglas MacArthur was able to retake the Philippines.

One of Clarence Carden nieces, Barbara Sue Bond, who now lives in Richmond, Va., was just a young girl when her Uncle Clarence died. This week she recalled sitting at her grandparents’ dining room table when the telegram came, notifying the family of his death. “His is a real story of bravery,” she said.

“Today’s young people know nothing of that war except what they read in history books. But, the men and women who fought in World War II were among our nation’s best,” she said.

Sue also remembers when her Uncle Clarence’s body was returned to the states. “His casket was brought to his mother’s home, where the family received friends. That was the custom then. His funeral was held at the Hampton Christian Church and his burial was in the Hall Cemetery,” Sue shared.

Sue also has two sisters, Priscilla Richardson and Nancy Bond, who are also quite proud of their dad and his brothers’ military service.

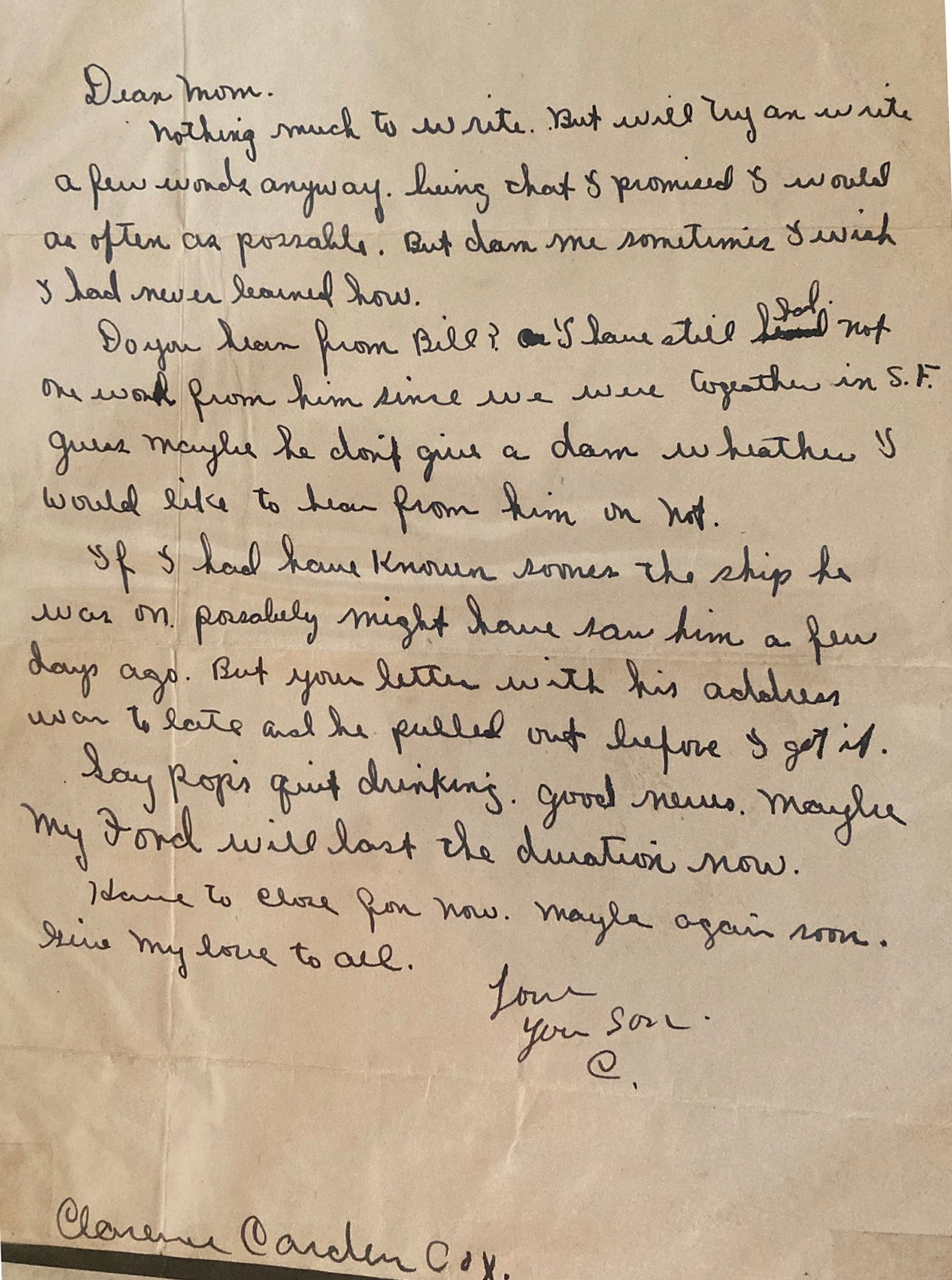

Sure also remembers her uncle as a very caring person. “He was always concerned about his family’s financial needs. In one letter dated April 4, 1944, Clarence wrote his mother: “Am sending fifty dollars in this letter and one hundred in a previous letter. Please let me know as soon as you ‘rec’ the two. Bank it or do as you wish.

“Nothing more to write. Maybe more next year. Give my love to all. Love C.’

Before joining the Navy and war effort, Clarence had worked at North American Rayon Corp. He earlier had attended Hampton High School.

Once the USS Johnston was discovered earlier this year laying on the floor of the Pacific Ocean after its burial nearly 77 years, the Canadian Oceanic Team, at the conclusion of its expedition, somberly laid a wreath in the vicinity of the battle site to salute the 186 lives lost that day.

We must never forget the battles fought in the name of freedom, nor must we forget men like Clarence Carden and his comrades who lost their lives that fateful day in October 1944 during the Battle of Samar.