When it came to abolitionism, Tennesseans didn’t have ‘free speech’

Published 2:44 pm Tuesday, October 12, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Tennesseans talk a lot about the right of free speech, and they should. But it’s interesting to note that free Tennesseans have not always had the right of free speech, at least not on all topics.

A couple of years ago I researched and wrote a book about slavery called Runaways Coffles and Fancy Girls. Some of what I discovered took me by surprise.

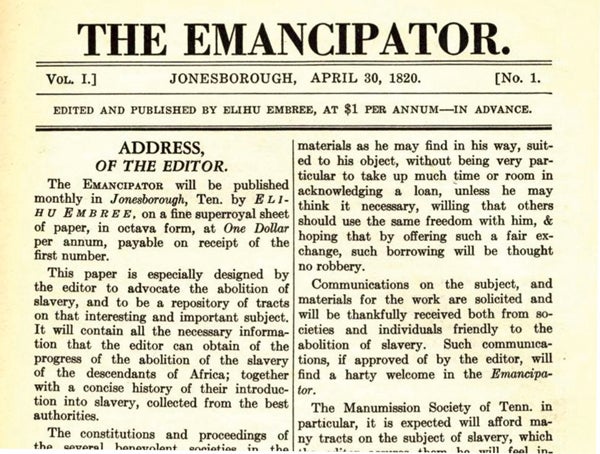

Before around 1835, it was perfectly legal to broadcast an opinion against slavery in Tennessee. In 1820, the Washington County seat of Jonesborough even had a newspaper entirely devoted to the cause of anti-slavery called The Emancipator. Elihu Embree published it, and according to its masthead, its purpose was “to advocate the abolition of slavery.”

However, a couple of points need to be made about this unusual footnote in Tennessee history. First of all, The Emancipator had a very short life span. Its publication ceased after only seven issues and didn’t continue after Embree’s death in December 1820, which leads to the conclusion that it suffered from lack of subscribers and advertisers.

It should also be pointed out that every other newspaper published in antebellum Tennessee — from the Knoxville Gazette of the 1790s to the Nashville Whig of the 1830s to the Memphis Daily Eagle of the 1850s — regularly published slave-related advertisements, from runaway slave ads to upcoming slave auction ads. They also had pro-slavery views which would shock people today. “It is as unnecessary as it is perilous to tamper with the relation of master and slave,” one issue of the 1854 Republican Banner opined.

After the 1831 Nat Turner Rebellion in Virginia, Tennessee clamped down on the expression of abolitionist views. In March 1836, the Tennessee General Assembly passed the following law (Article VII, Section 2682 of Tennessee Code):

“No person shall, in this State, write, print, paint, draw, engrave or aid or abet in writing, printing, painting, drawing or engraving on paper, parchment, linen, metal, or other substance with a view to its circulation, any paper, essay, verses, pamphlet, book, painting, drawing or engraving, calculated to excite discontent, insurrection or rebellion amongst the slaves or free persons of color.”

The punishment for breaking this law was between 5 and 10 years hard labor.

This law meant it was legal for a Tennessean to write anti-slavery opinions in a personal diary. But the minute a person posted them on a wall, he or she was breaking the law.

The law meant newspapers were not free to publish opinions that advocated the elimination of slavery.

The law also meant that it was (technically, at least) illegal to distribute a copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was seen as an insurrectionist document in Tennessee. In fact, when Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel first came out, several newspapers in the north published sample chapters from it. I have found no such excerpts published in Tennessee — only harsh criticisms of the book containing words such as “false,” “vulgar” and “disgusting.”

It’s impossible to know how many times people were charged with violating Tennessee’s “incitement” law between 1836 and the Civil War, when the slavery matter was settled. But I do know that in 1846, a Maury County man named Alexander Billings was tried, but not convicted, for circulating a painting that was allegedly meant to incite slaves to rebellion.

I bring all this up because today there is an assumption that the U.S. Constitution has always guaranteed free Tennesseans the right of free speech. Suffice it to say that the right of free speech has evolved.