Rhea map full of fascinating information about Tennessee

Published 2:04 pm Tuesday, February 8, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Do you like maps? I always have, but my son thinks there’s something wrong with me because I like maps so much. I’ve been known to download maps on the internet and stare, shaking my head in amazement at how much information can be gleaned from them. “Dad, are you still looking at that map?” my son has been known to ask.

My favorite Tennessee map was produced in 1832 by the cartographer Matthew Rhea. Rhea’s map was a detailed work of art which, when originally printed, was about nine feet long and three feet high. That’s why its digital file (which can be downloaded at both the Tennessee State Library and Archives and U.S. Library of Congress) is so massive.

I’ve done entire inservices on Rhea’s map, showing parts of it on power point slides that ooh and ahh teachers. I can’t be quite so visual in this column, but here are some of the fascinating tidbits from Rhea’s map:

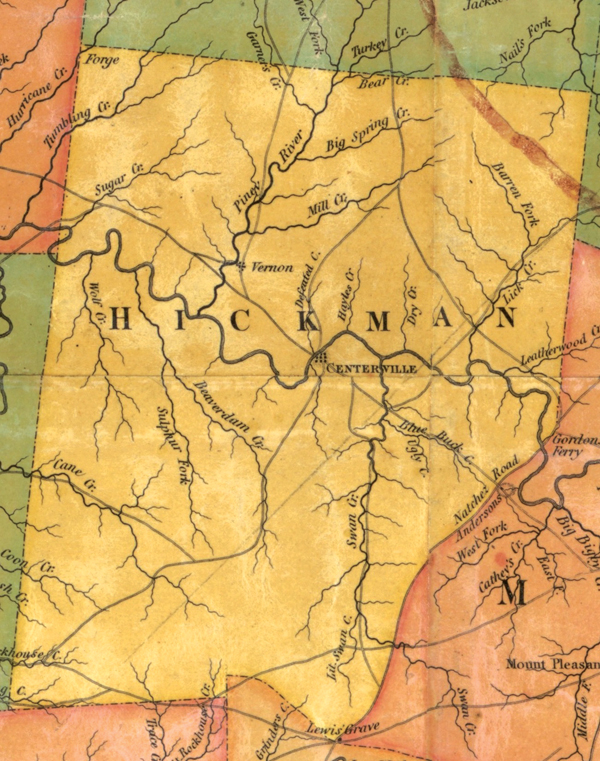

Rhea did a wonderful job showing the locations of creeks. On his map, I count 15 creeks in Hickman County alone — from the wonderfully named Swan Creek to the less wonderfully named Ugly Creek.

There are quite a few county seats that have moved, and some of the county seats in 1832 are pretty much abandoned now. Examples included Monroe (Overton County), Montgomery (Morgan County), Reynoldsburg (Humphries County) and Perryville (Perry County).

Reelfoot Lake, formed by the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811-12, is not shown on the map. The only indication that there is something unusual about the terrain in the northwest part of Tennessee is the use of the phrase “flooded land” three times over parts of Obion County and once over Dyer County.

I was surprised by the number of Indian mounds and prehistoric ruins that made Rhea’s map. The site of Fort Loudon (destroyed in the 1750s) is mapped, as is Stone Fort (now known as Old Stone Fort) and “Mound Pinson” (now known as Pinson Mounds).

The only feature in Nashville that made the map is the state penitentiary. That’s right — in 1832, in Matthew Rhea’s opinion, the most important thing in Nashville was a prison.

One of the versions of Rhea’s map that you will find online has markings on it. Apparently, someone who owned the map in the 1830s hand-wrote the location of every obstacle along the Tennessee River, starting in Knoxville. According to the map there were more than 50 such places, and the person who wrote on the map apparently named most of them for settlers who lived in the area. Rhea County had seven navigational obstacles (Gillespie’s, Walton’s, Well’s, Kelly’s, Lea’s, Hiwassee and one I can’t make out.) Just downstream from present-day Chattanooga, this person noted the exact locations of well-known Tennessee River obstacles such as the Suck, the Boiling Pot and the Skillet.

There are parts of Tennessee that today have towns and cities in them that apparently had no towns or cities in them in 1832. Places in and near the south Cumberland Plateau such as Tullahoma and Monteagle didn’t exist yet. The same can be said for East Tennessee communities such as Pigeon Forge and Gatlinburg. As you see the open space on the map, it does make you wonder what the mountains looked like at that time.

The map shows the locations of mills and forges throughout the state, but some counties get more coverage in this regard than others. Rhea showed 10 mills in Hardeman County, but only one in McNairy County and none in Henderson County. Meanwhile, 16 Carter County forges made Rhea’s map!

Since it didn’t exist in 1832, the city of Chattanooga didn’t make Rhea’s map. In fact, the only towns mapped along the Tennessee River, south of Kingston, are Washington (in Rhea County), Dallas (in Hamilton County), and the Chickamaugan Indian village of Nickajack. Today, none of these communities exist.

Speaking of the Hamilton County community of Dallas: Since it appeared on Rhea’s map, we know that Dallas, Tennessee, predated Dallas, Texas. The next time you meet a swaggering Texan, point out that his state stole the name “Dallas” from Tennessee. I’m sure that will go over well.