Crockett’s saga full of fascinating tidbits

Published 1:28 pm Monday, May 2, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Everyone has heard of “Davy” Crockett, but not everyone has a clear idea of what he did. Here are some of the high points:

Today, people often refer to this man as “Davy,” but he never went by that name. The reason we call him “Davy” is because of a song written in the 1950s, when there was a national craze for all things Crockett.

David Crockett is one of the most famous people to ever come from Tennessee. But he was never the president, nor governor, nor general. The highest political rank Crockett achieved was member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Crockett was born on August 17, 1786, which means he was born before Tennessee existed. Technically, Crockett was born in what we now refer to as the “Lost State of Franklin” (that’s another column)!

Crockett’s father John Crockett was not a good provider. In fact, at one point, Crockett’s father “leased” him to another man to help pay his debts (a practice not uncommon at that time).

Crockett was not always successful with the girls. In his autobiography he describes two instances where he ended up with a broken heart. “My heart was bruised, and my spirits were broken down,” he later wrote about one of these instances. “I bid her farewell, and turned my lonesome and miserable steps back again homeward.”

Crockett was restless, to say the least. He was born along the Nolichucky River (in present-day Greene County) and his father moved his family to a tavern (in Hamblen County). He spent about three years as a teenager living alone in various parts of Virginia. As an adult, David lived in what are now Jefferson, Lincoln, Franklin, Lawrence and Gibson counties of Tennessee.

Crockett twice volunteered to fight in the Creek Wars. He proved valuable as a scout and hunter, and he also saw some combat. But as fate would have it, Crockett missed both the Battle of Horseshoe Bend and the Battle of New Orleans.

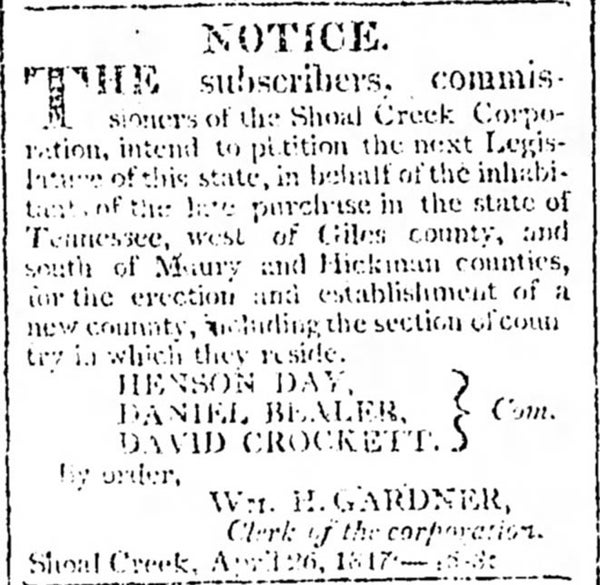

Crockett’s political career began in Lawrence County, where he was elected colonel of the local militia and later state representative. In fact, according to a small item in the July 1817 Nashville Whig, Crockett was one of the county’s four founders.

Crockett married twice. His first marriage, to Polly Finley, bore three children. She died shortly after he got back from the Creek Wars and is buried in Franklin County. A few months later Crockett married Elizabeth Patton. David and Elizabeth had three more children, but do not appear to have had a close marriage, as he was almost away hunting or in Congress.

Like his father, Crockett was a failure as a businessman. One of his schemes was a mill, distillery and gunpowder factory in Lawrence County. That venture failed when Shoal Creek flooded. A few years later, Crockett went into the timber business in Gibson County. The plan was to chop down hundreds of trees, cut them into lumber, float them down the Obion and Mississippi rivers and sell them in New Orleans. Unfortunately, the flatboats on which Crockett was delivering his timber capsized in the Mississippi, and he nearly drowned.

When he was originally elected to Congress in 1826 (from West Tennessee), Crockett was an ally of Andrew Jackson. But Crockett broke with Jackson and voted against the Indian Removal Act in 1830. From this point onward, Jackson and Crockett were political enemies.

Crockett became nationally famous because of stories he would tell other Congressmen and reporters about hunting bears, fighting in the Creek War, floating down the Mississippi and other things. Reporters wrote articles about him, and he became one of the best-known personalities in America.

In 1831 a play called “The Lion of the West” became a hit in New York. Its main character, Colonel Nimrod Wildfire, was a storyteller wearing a buckskin shirt and coonskin cap, clearly based on David Crockett. This play resulted in the publication of a “biography” of Crockett that he didn’t write, had nothing to do with, and from which he made no money.

Crockett’s best friend in Congress was Thomas Chilton of Kentucky, who broke with President Jackson in much the same way Crockett had. Chilton ghost-wrote Crockett’s bestselling 1834 autobiography A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee. It is hard to know how accurate this book is, especially since Crockett had a tendency to stretch the truth. He claims to have killed more than 100 bears in a seven-month span in West Tennessee, for instance. But Crockett’s humor comes through in the book. He admits that as the years passed, he was “better at increasing my family than my fortune.” And speeches in Congress, Crockett says, are so boring that “it’s harder than splitting gum logs in August to stay awake.”

So why did Crockett leave Tennessee? In 1834, he lost his bid for re-election to Congress. Having heard his friend Sam Houston talk about Texas, Crockett decided to go there himself. “Since you have chosen to elect a man with a timber toe to succeed me, you may all go to hell and I will go to Texas,” he reportedly said just before he left (in reference to his political opponent’s wooden leg). Not long after he arrived, he enlisted in the army, went to the Alamo, and died there, in March 1836.

Bill Carey is the founder of Tennessee History for Kids, a non-profit organization that helps teachers cover social studies.