Stories abound regarding Tennessee’s western boundary

Published 8:53 am Tuesday, May 10, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Bill Carey

There’s a story behind every boundary — why it’s here and not over there, why it shifts this way and then that way.

Take Tennessee’s western border, for instance. Many people assume that Tennessee’s western boundary is the Mississippi River, but they are wrong. Over the years, the river has moved, causing confusion about where the border is. According to the U.S. Supreme Court, the western border of Tennessee cannot be moved because of the movement of the river. Therefore, Tennessee’s boundary with Arkansas lies where the channel of the Mississippi River was in 1836, when Arkansas became a state. Tennessee’s boundary with Missouri is where the river was when Missouri became a state in 1821.

Because of this rather unusual situation, there are many stories and legends about places where the Mississippi River has moved, but the border has not. The best source of this material is a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ book called Historic Names and Places of the Lower Mississippi River by Marion Bragg.

I’ll start in Tennessee’s northwest corner and work my way south.

Kentucky Bend is a part of Fulton County, Ky., surrounded on three sides by the Mississippi River and one side by Lake County, Tenn. Few people live there today. Mark Twain, in his book Life on the Mississippi, described a feud between two families who lived there and attended the same church. “Half the church and half the aisle was in Kentucky, the other half in Tennessee,” he wrote. “Sundays you’d see the families drive up, all in their Sunday clothes, men, women, and children, and fill up the aisle, and set down, quiet and orderly, one lot on the Tennessee side of the church and the other on the Kentucky side.”

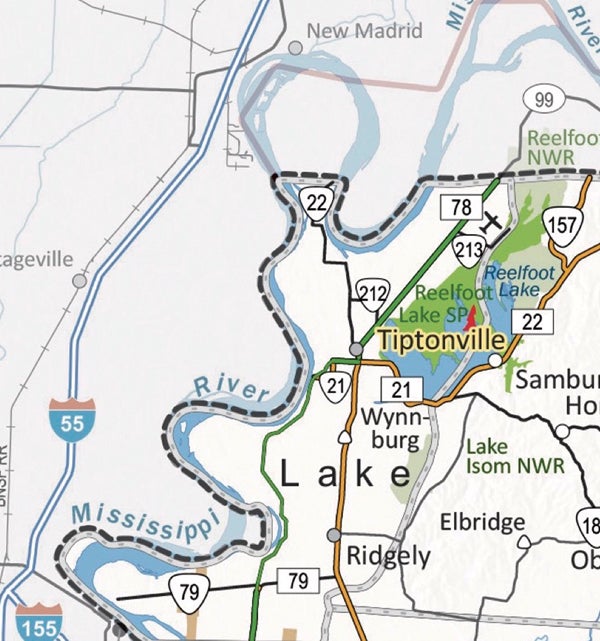

Moving downstream, the Lake County seat of Tiptonville used to be along the river, but the river has moved. Now Tiptonville is more than a mile from the river.

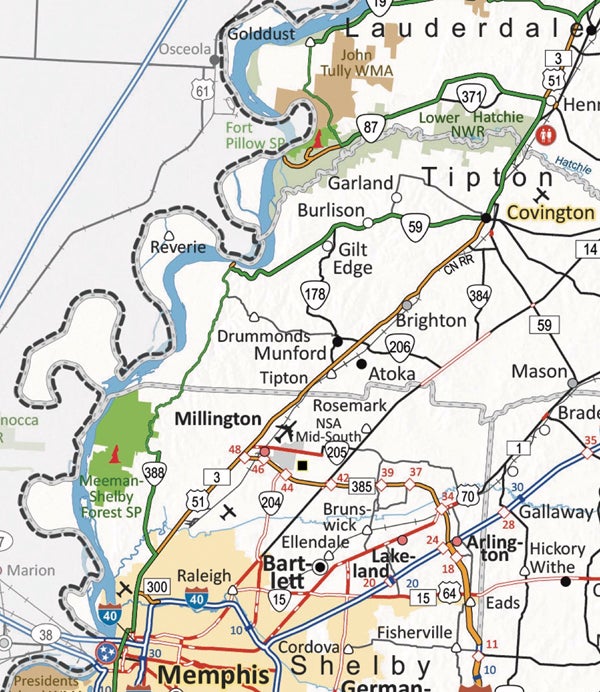

Shifting south, there was a busy river town called Ashport in Lauderdale County with “several small warehouses and a big steam-powered sawmill,” Bragg wrote. However, the river eventually washed away most of the original 200-acre town.

Downstream and around the bend from Ashport is Plum Point, once one of the most dangerous places on the Mississippi. “A multitude of snags, half-concealed tree trunks, and sandbars gave even the most adventurous pilot cold chills, and the currents that foamed around the point were enough to frighten a timid flatboatman half to death,” Bragg wrote. Over the years, the Army Corps of Engineers made Plum Point safe for boats.

Just downstream from Plum Point was a Confederate fort called Fort Pillow. As any Civil War buff will tell you, Fort Pillow fell to Confederate cavalry led by Nathan Bedford Forrest in April 1864, in one of the Civil War’s most controversial battles (that’s another column). Since then, the river has moved so much that you can hardly see it from Fort Pillow State Historic Park today.

Continuing southward, the Mississippi River passes the former site of the town of Randolph. Once a rival to Memphis, Randolph declined because of (among other things) a shift in the river current. Once big enough to have hotels and a newspaper, Randolph now consists of a few houses and a historic marker.

Just downstream and across the river from the former site of Randolph is the community of Reverie. Due to the movement of the river, this Tipton County town has the distinction of being the most populous Tennessee community on the west side of the Mississippi River. (However, let’s put this in context: Wikipedia claims that in 2001, Reverie’s population was 11. So we can safely say that Reverie’s status as the only Tennessee community on the wrong side of the river has not proven to be an economic boon.)

Continuing southward, there are many places in Tipton and Shelby counties where the river has straightened itself over the years, leaving much Tennessee land west of the river. One of these places is Centennial Cutoff, where the river made the shift during a single day in the year 1876.

Centennial Cutoff removed a bend in the river called “Devil’s Elbow” and created a new island known as Island 37. Because of confusion about which state owned the island, it became a harbor for lawbreakers, which is why the Arkansas militia raided it in July 1915.

That raid led to one of the U.S. Supreme Court decisions regarding the location of the border. In the 1918 case known as State of Arkansas v. State of Tennessee, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the piece of land then known as Island 37 was still part of Tennessee. Today the river has completely shifted to the east side of what was once known as Island 37, and the land is attached to the Arkansas side but still part of Tennessee.

Bill Carey is the founder of Tennessee History for Kids, a non-profit organization that helps teachers cover social studies.