Local musician: ‘Loretta Lynn was every bit a lady’

Published 3:46 pm Friday, October 14, 2022

1 of 2

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Angela Cutrer

Elizabethton Star

The aura of country music legends hints they are celestial bodies too high for locals to ever hope to meet, much less make friendships among them.

Not so, says local musician Randy Grindstaff, at least not with the original country music artists who lived and worked in Nashville.

And especially not so when considering the immortal Queen of Country Music, Loretta Lynn, whose music and life story will continue to awe fans new and old long after her death Oct. 4.

Grindstaff knew Lynn — he played banjo for her during a concert years ago quite by accident. And four decades later, Grindstaff was in the crowd in Bristol as Lynn came back to this area to perform.

“Hey, I know you,” Ms. Lynn said, pointing at a shocked Grindstaff. “How ya doing?”

That was the kind of woman — and star — Loretta Lynn was. Considering that she’d traveled the world as a performer and met thousands of people, Lynn still recognized a young man now grown as one who had played with her years ago.

Grindstaff never forgot that.

“Loretta Lynn was one of a kind,” he said. “I’ve been around all the old country performers and met all those women stars and became friends with them. Loretta Lynn was one of the nicest people you’d ever meet. Down to earth — not a star personality. She was every bit a lady.”

Getting his start

Grindstaff was just your average East Tennessee boy when he would tag along with his parents as they visited local friends. The gatherings were always musical, mainly country and mountain music that young Grindstaff found old-fashioned.

“I didn’t like it much,” he said. “My mother sang and played the guitar, but I wasn’t into the music that much — it was ‘country.’”

However, one Saturday night at a musical gathering, Grindstaff was struck by a sound he couldn’t recognize. “It was like a lightning bolt hit me,” he said. “I asked my mama what it was and she said it was called a ‘banjo.’ I told her if she’d get me one of those, I’d learn how to play it.”

Though surprised by her son’s sudden musical interest, she did get him that banjo and he kept his word. Up every morning two hours before school, Grindstaff practiced. He’d play the old 45-records, setting the needle to just the right spot, then lifting the needle to learn the cords, and then back again to listen for more.

One day Grindstaff went to the local radio station and asked if he could sit in the background, just to listen and learn as live bands played. It was this education in playmanship and style that led him to playing with others as he expounded on his self-taught banjo training.

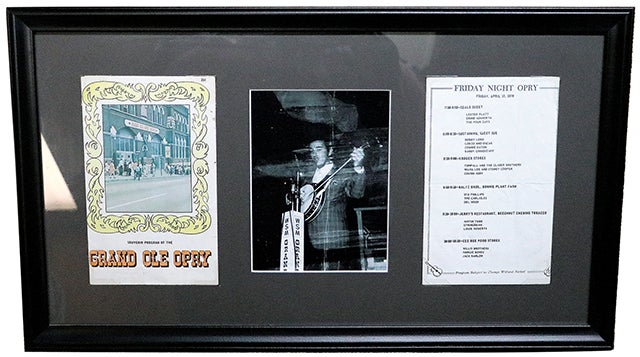

Grindstaff’s grandparents once took him to Ryman Auditorium and the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville. It was there Grindstaff asked the Lord if perhaps one day he himself might play there.

Grindstaff’s experience grew as he played with groups. On one trip with his parents for a gig, a snowstorm almost turned them back when Grindstaff got a feeling he needed to keep going. It was at this performance he met a man who gave him his card, saying he was impressed with Grindstaff’s playing. He requested a recording and a photo, which Grindstaff later sent him.

“One day my mother woke me up to news I’d gotten a letter from the Grand Ole Opry,” Grindstaff said. The letter gave the date and time Grindstaff was expected to go on stage. The man who gave him his card was the president of the bank that owned the Opry. “I was glad I hadn’t turned back during that snowstorm,” Grindstaff said. “I was on a path — I couldn’t turn back.”

The Grand Ole Opry

The Lord had blessed him by granting his wish. That first visit initiated Grindstaff’s love for country and bluegrass music, and the people who produced, sang and played it. He met Bud Wendall, the Opry’s manager, who welcomed him into the Opry “family.”

“That’s how they were back then,” Grindstaff said. “It’s like a family with the warmest, nicest people. They introduced me around and complimented me for being the first five-string banjo player to be invited to play at the Opry.

“Minnie Pearl was a fantastic lady, elegant and well educated. I even told Keith Whitley he ought to try country music, and he did! He was a nice man, and so talented.

“I walked into Roy Acuff’s record store to find the man himself there. He said ‘you must be pretty good [a banjo player] if you were invited to the Opry.’”

Grindstaff must have been, because he returned often and made many friends, including Ricky Skaggs, Bill Anderson and Bill Monroe, who called Grindstaff to talk just two weeks before Monroe’s death.

“Nine out of 10 of every one of those people were just fantastic human beings,” Grindstaff said. “You become a part of them and they accepted you. And when you did, you didn’t use filthy language or drink in front of them. They wouldn’t have it. They wouldn’t put up with any disrespect. That would make them turn around on you. They were true ladies and gentlemen who didn’t put up with that kind of stuff. They didn’t like arrogance; they didn’t boast. They figured that if you were there at the Opry, you didn’t have to say anything about it. Your talent got you there already.”

Nashville atmosphere

Nashville was a different place back then — earthy, raw, real, rural. But though it was a simpler time, there was real danger, too.

Other men Grindstaff enjoyed keeping company with included Louis “Grandpa Jones” and David “Stringbean” Akeman.

“[Stringbean] gave me his spot [on the Opry] one night, saying he’d been there since the place started, so he wanted me to be able to do another number,” Grindstaff said of the celebrated performer of the old-fashioned banjo playing, “clawhammer,” which is different from the way Grindstaff played.

“He was a nice man. He really was. I remember patting the bib of his overalls, and warning him about keeping his money in there.”

“Ain’t no body gonna bother ol’ Stringbean,’ the man said to Grindstaff, laughing about a need to worry. Two weeks later, Stringbean and his wife were murdered at their home by burglers. Grandpa Jones, who’d stopped by to pick up Stringbean to go fishing, found their bodies.

Remembering the past

Grindstaff has been retired now for years. He took up a job with the Tennessee government and retired from there as well.

Though he misses the glamorous life of country music, it’s way different now than how he remembered it. “Ralph Stanley [once] told me that we were watching an art form that was being lost,” Grindstaff said sadly. It seemed Stanley was right. These days, you couldn’t get near a country music star, much less speak to one.

But back in the day, Grindstaff got to play with the great Loretta Lynn in Elizabethton. “I did the whole show with her,” Grindstaff said. “Some songs needed a banjo and some didn’t, but I did the whole show with her.

“Afterward, I was getting ready to leave when she said, ‘Where you going? We have a private room at the VFW and we’re gonna have supper and I want you to come.’ So I went and sat elbow to elbow with her.

“They brought out steaks and salad and baked potato,” he remembered, and then laughed uncomfortably. “I grew up here in the mountains, okay? I didn’t know how to eat a steak or a salad or a baked potato. So, I just watched how the others did so I would know how to eat them.”

The “Coal Miner’s Daughter” single came out as a 45 on Oct. 5, 1970, becoming a No. 1 one hit on the Billboard country chart. Lynn wrote the song and the background vocalists were the Jordanaires.

On an online video dated Oct. 20, 1985, Roy Acuff introduces Lynn on stage at the Grand Ole Opry to sing three songs, including “Coal Miner’s Daughter.” Before she began her second song, she looked down into the audience in front of her and said — to a total stranger — “Hi, there.”

That was Loretta Lynn — always wanting to make others feel comfortable. Behind her, Acuff mouthed the words to her song as she sang — it was at his insistence she was singing his favorite song that night. “I truly think this is the one of the finest country songs written in a number of years and the way she can perform it makes it out of this world,” Acuff said to the audience.

Grindstaff remembered how, as a young self-taught banjo player, he got to play with Lynn because he was in the right place at the right moment with the right skills. It spurred his long career and his fond memories.

“The music comes from your personality — it comes out through you,” Grindstaff said. “If a bluegrass musician hasn’t lived it, it doesn’t transpire and it never will. They are good, but that true form is missing.”

Grindstaff’s son, Daniel, followed in his father’s footsteps to become a well-known and beloved banjo player himself. A family man living in Elizabethton, Daniel grew up with bluegrass legends while tagging along with his dad to gigs.

“I’m not telling my story for a pat on the back,” Randy Grindstaff said. “I was fortunate to live it. I’m doing this for my kids and grandkids. I was proud that the Lord let me do it. Maybe my grandkids would be proud, too.”