‘Runaway wife’ ads in early Tennessee newspapers

Published 1:50 pm Monday, January 9, 2023

1 of 1

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Bill Carey

I’ve heard it said that families were happier “in the old days.” However, newspapers prove that not every household was blissful. They also remind us that, when it comes to legal status, women have come a long way.

There are several types of runaway ads published during Tennessee’s antebellum era. There were runaway horse ads. During periods of military activity (such as the early wars against Native Americans) there were deserter ads, offering a reward for the return of a soldier who abandoned his military unit. At a time when it was a big part of Tennessee’s economy, there were runaway indentured servant ads. There were, I’m sorry to say, runaway slave ads (in fact, I wrote an entire book about Tennessee’s runaway slave ads called Runaways, Coffles and Fancy Girls.)

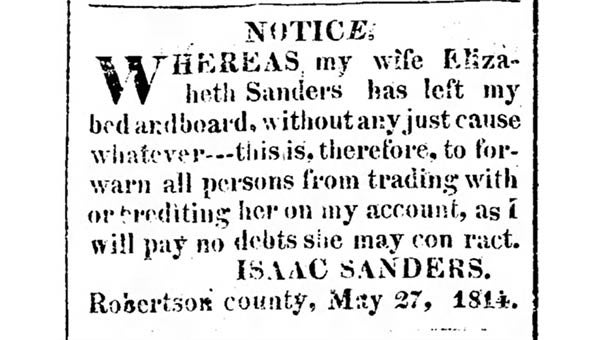

None of these have taken me by surprise. But the “runaway wife” ads have. A typical one can be found in the November 9, 1805, Mero District Advertiser. “I do hereby forewarn all persons from crediting my wife Polly Cartwright, on my account, or harboring at her, as she has left my bed and board without any just cause,” the ad states. “I am therefore determined to pay no debts of her contracting, and will prosecute any person harboring her, with the utmost rigor of the Law. Robert Cartwright.”

I’ve found similar ads published by John Smith of Knox County regarding his wife Margaret (1792); Isaac Sanders of Robertson County regarding his wife Elizabeth (1814); Richard Crunk of Dickson County regarding his wife Mary (1825); Zebulon Hassell of Hickman County regarding his wife Unity (1836); James Bland of Lincoln County regarding his wife Permalia (1857); and the list goes on and on.

The wording of these ads is generally the same: The husband claims his wife has left his “bed and board,” often “without any just cause.” The husband warns merchants from “trading with or crediting her” on his account, saying he will pay none of her debts from this day forward.

The purpose of this column is not to air out centuries-old marital dirty laundry, but to make a point about life on the American frontier. We can talk all we want about how much women contributed to the household and to society in early frontier history. Legally, however, women were second-class citizens.

A woman who left her husband did have more legal rights than a runaway slave or indentured servant. (She wasn’t thrown in jail, for instance.) But a runaway wife didn’t have the same rights as her husband. “Married women generally were not allowed to make contracts, devise wills, take part in other legal transactions, or control any wages they might earn,” explains Indiana historian Tim Crumrin in an essay for the Conner Praire living history museum in Indiana. “One of the few legal advantages of marriage for a woman was that her husband was obligated to support her and be responsible for her debts.”

The frequency of “runaway wife” ads also reminds us that the frontier economy didn’t run on cash. Local merchants extended credit to everyone and collected monthly or even seasonally.

These runaway wife ads may, to us, simply appear to be an attempt by a jealous husband to shame his wife. But they were also the frontier equivalent of, well, “canceling the credit card.”

At a time when all the assets of a marriage were considered the property of the husband, and at a time when most occupations were closed to women, the implications of such ads were clear. In the old days, a wife who left her husband needed financial help from someone else.

If this column hasn’t offended you yet, keep reading.

At a time when West Tennessee was THE frontier, it was difficult for the first wave of settlers to find available ladies. In any case, here is an advertisement in the June 12, 1824 Jackson Gazette:

“$2000!!! WANTED IMMEDIATELY, a YOUNG LADY, of the following description [as a wife]—with about $2000 as a patrimony, sweet temper, spend but little, be a good house-wife, and reasonably handsome.—And as I am under 30 years of age, I hope it will not be difficult to find a good wife.”

The ad was signed “A.B.” We don’t know if he meant it as a joke, and we don’t know if anyone ever responded to his advertisement. But we do know that times have changed.

Bill Carey is the founder of Tennessee History for Kids, a non-profit organization that helps teachers cover social studies.