Tennessee’s Coal Creek War Tested 13th Amendment

Published 2:31 pm Monday, April 10, 2023

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Editor’s note: This is second in a series of columns about topics currently slated to be deleted from Tennessee’s eighth-grade social studies standards.

Many people believe the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution outlaws slavery, but that’s not exactly true. The Thirteenth Amendment bans slavery “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” A long series of nationally publicized events known as the Coal Creek War tested this concept.

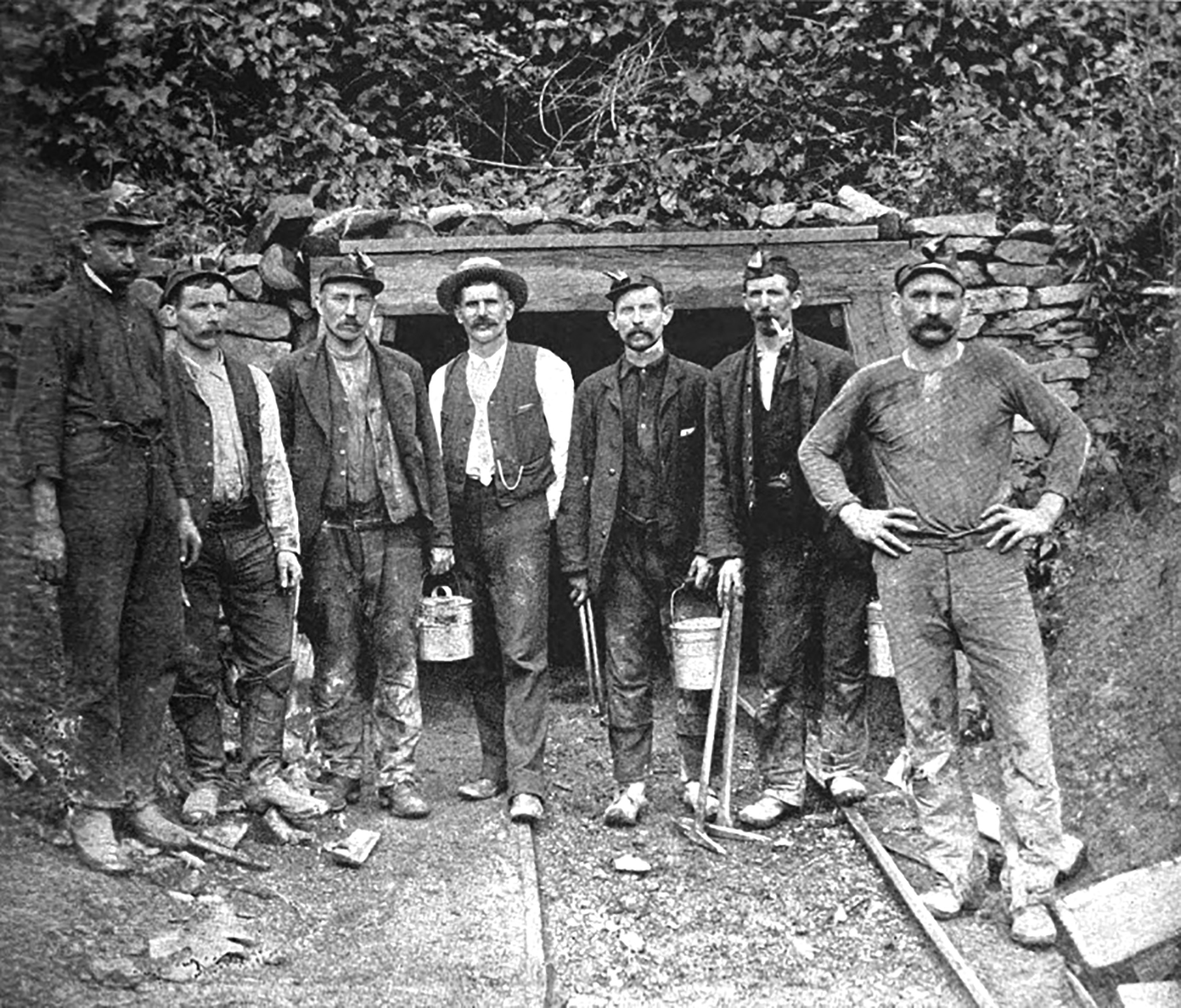

The Anderson County town of Coal Creek was founded when the railroad first came in, around 1870. Like many towns on or near the Cumberland Plateau, it was a mining town where men walked underground in the morning, worked hard all day, and were paid based on how much coal they mined.

People often assume coal miners were paid poorly. Barry Thacker, who has studied the area extensively and who makes presentations to teachers about its history, claims otherwise. “In the 1890s, wages that coal miners were getting for two days’ work would buy an acre of land in the Coal Creek area,” he says. “It was tough and dangerous work, but the miners were paid well, certainly by their standards of that era.”

The use of inmates to mine coal near Coal Creek started in the mid-1870s, when the state operated a branch of the penitentiary there. However, in 1891, things went a step further. After a pay dispute, the Tennessee Coal Mining Company fired all its miners at Coal Creek and nearby Briceville and replaced them with inmates it leased from another company as part of a “convict lease” program.

In the summer of 1891, the Tennessee Coal Mining Company sent more than 100 convicts, escorted by armed prison guards, to Coal Creek. The convict miners tore down the company-owned homes of free miners and built a stockade in which they would be housed.

Free miners decided to fight for their jobs. The next day, about 300 armed miners surrounded the stockade. The guards surrendered without firing a shot. The convict miners and guards were marched to the Coal Creek train station and sent to Knoxville. Miners also sent a telegram to Tennessee Governor John Buchanan, saying their action was “a necessary step in the defense of our families from starvation and our property from ruin.”

Governor Buchanan responded by calling out the Tennessee National Guard and going to Briceville himself. The reception he got there from 600 miners, on July 16, 1891, will probably go down as the single most uncomfortable moment ever experienced by a Tennessee governor. “Gov. Buchanan said he had no speech to make, but also said that he did not make laws but executed them,” The New York Times reported.

Under National Guard escort, the convict miners were sent back to Briceville. Again, the local coal miners took over the stockades, this time in both Briceville and Coal Creek, and sent the convicts back to Knoxville.

In early September, Buchanan called the Tennessee General Assembly into special session and asked them to repeal Tennessee’s convict labor system. The legislature met, but did nothing of the kind.

In November 1891, miners took action yet again by capturing stockades in Briceville, Coal Creek and Oliver Springs. Instead of putting the 460 convicts on a train, they turned them loose. Miners then set fire to the stockades in Briceville and Oliver Springs.

The “war” was on. For the next few months, there were reports of company officials, prison guards and convicts being shot at by unknown snipers from nearby hills. There were also reports of the National Guard taking shots at local citizens and miners. In an attempt to placate the citizens of Coal Creek, the National Guard built a fortress called Fort Anderson overlooking the town.

These events were well publicized in national newspapers. Since more than half of the inmate miners in the middle of the controversy were African Americans who had been arrested and sent to East Tennessee from Memphis and Nashville, some newspapers pointed out that these black miners were no better off than slaves a generation earlier. “The leased convict is worse off than the old-time slave, because the slave owner always had as much interest in keeping his slave in a workable condition and making him last as long as possible as he had in keeping his horses in that condition,” one New York newspaper said.

State militia finally put down the rebellion and arrested several of the leaders of the free miners in August 1892. A few months later, after Governor Buchanan was replaced by Peter Turney, the new governor chose not to renew the state’s contracts to lease convicts to private mining companies. Tennessee became the first state in the South to get rid of its convict lease program – one of the prison reforms that came out of the so-called Progressive Movement.

The state of Tennessee replaced the revenue lost from convict leasing by building Brushy Mountain State Prison and Coal Mine in Morgan County. Convicts mined coal there until the 1960s.

As for the town of Coal Creek, it still exists, but has changed its name twice in an attempt to improve its image and lure businesses – first to Lake City, and more recently to Rocky Top.