The 30-foot cross that could be seen for miles

Published 2:33 pm Wednesday, May 31, 2023

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

There’s a hill south of downtown Nashville that contains Carter-Lawrence Elementary School and several sports fields, one of which is Belmont University’s home baseball stadium. On a recent Friday, I took my dog to the top of it and saw joggers, people playing softball and the students taking part in their annual field day. It was a wonderful place to be.

However, one hundred years ago this week, the Ku Klux Klan held its most widely viewed meeting ever in Middle Tennessee there.

On the night of June 1, 1923, residents of Nashville were mesmerized by the sight of a huge cross lit by incandescent lights on the hill.

The Nashville Tennessean had a front-page article about the event the next day. “Approximately 1,000 Klansmen, dressed in white . . . paced slowly along the outposts and inner circles of the carefully guarded peak, while an initiatory class of 500 persons knelt, and with upraised arms swore allegiance to the Ku Klux Klan as a ‘body created for the reservation of 100 percent Americanism.’”

According to the story, an estimated 5,000 people migrated to the base of the hill to get a closer look. They were stopped by members of the Klan from proceeding past a pre-designated boundary – although reporters were allowed to go closer.

The front-page story reminds us that the KKK was at the peak of its power a century ago. It was a major force in state and national politics and had millions of members across the U.S. (membership estimates vary). Unlike the Klan of the late 1900s, which held meetings at secret locations, the Klan of a hundred years ago was hard to avoid.

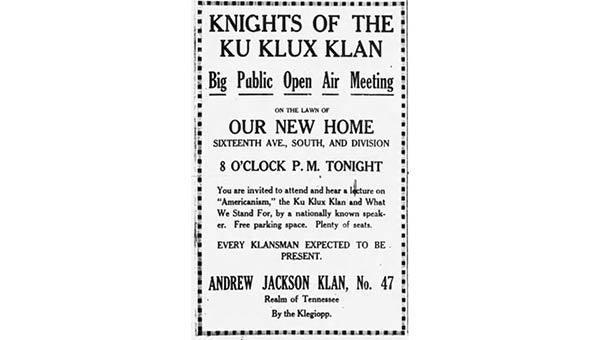

In Nashville, the Andrew Jackson chapter had a well-publicized headquarters and bought ads in the paper. “You are hereby notified that the next open air meeting will be held Friday evening, June 22, at 7:30 p.m. at our new home, corner First and Cleveland Streets,” ran an ad in the Tennessean only a few weeks after the June 1 meeting. On June 22, a reported 200 new members joined up.

The next year, 1924, the Klan signed a lease on a mansion and surrounding property at the corner of Sixteenth Avenue and Division Street, then spent a reported $60,000 to convert its large backyard into a meeting space for 6,000 people. (This would have made it, by far, the largest gathering space in Nashville at that time.) Atop the mansion, the Klan placed a large cross, lit by 300 light bulbs.

The Tennessean ran several small items about events at Nashville’s Klan headquarters during the next year or so. The day after Thanksgiving 1924, a musical program was staged there, attended by 200 women who were all given carnations. That night, 350 more members were initiated, bringing local membership up to about 2,000. In 1925, Nashville’s morning newspaper had small articles about revivals, lectures and Daughters of the Confederacy gatherings that took place at Sixteenth and Division. “The Protestant public is invited,” mentioned one article about a lecture on evolution.

However, as stories spread about KKK atrocities, the Klan’s reputation declined precipitously. The cozy relationship between the organization and the Tennessean appears to have vanished by 1927. The Klan abandoned its Sixteenth Avenue location within a few years, and the city converted the site into a playground in 1939.

A generation later, the Country Music Association began raising money for a Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. In 1963, Nashville Mayor Beverly Briley announced that the city was donating a piece of land to the cause consisting of “a small park at the corner of Sixteenth Avenue South and Division Street, which provides a commanding location.”

At the time, there was no mention of the fact that the land had previously been the Nashville Klan headquarters. When I first encountered these newspaper clippings around 2002, I asked many knowledgeable people whether they knew the Country Music Hall of Fame had sat on land that had once been a Klan venue. The only person who knew this was Andrew Benedict, the longtime president of First American National Bank. He said he knew about the history of the site because he had helped raise money for the hall of fame in the early 1960s. Benedict, who died in 2008 at the age of 94, was the only person who knew.

Suffice it to say that it is interesting what we choose to remember about history.

Thanks to Allen Forkum, editor of the Nashville Retrospect, for his assistance in researching this column.