Former resident shares benefits, importance of urban forest

Published 4:39 pm Friday, May 8, 2020

1 of 2

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

BY ANDREW CARRIER

I grew up in Elizabethton, spent my childhood days on the banks of the Watauga River and my high school Friday nights in black and orange. I’ve hiked the nearby Appalachian Trail with my best friends and taken in those magical small-town summer evenings with my family. To put it simply, I love this town and the people and character it represents. In an effort to repay some of what Elizabethton has given me over the years, I felt compelled to write an article with some ideas for how we can support our city for the future. If you’ll allow me, I’d like to share with you the benefits and importance of the urban forest, what they can do for our city, and how we can work together to build them up.

THE TRIPLE BOTTOM LINE

Urban forestry: sounds rather oxymoronic doesn’t it? We don’t typically associate urban places with their forestry resources, but as it turns out these are some of the most powerful tools we have to create better, more sustainable cities. Modern urban forestry seeks to maximize the benefits that trees provide to cities in three core areas (economic, social, environmental) and refers to them collectively as the “triple bottom line.”

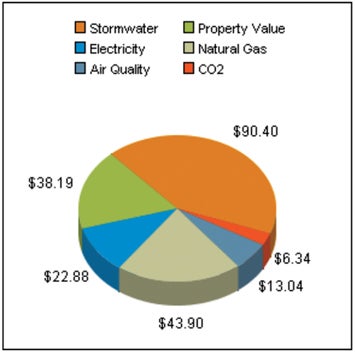

It may seem strange to consider that a forest can bring value to a place without the act of harvesting its timber, but that is exactly what the urban forest brings to our city in several ways. First, consider the ecosystem services provided by the urban forest. Street trees and rain swales can be used to mediate storm water, reducing demand at treatment plants and thereby saving money. Deciduous trees planted in strategic locations around a home or business can provide shade in hot summer months and allow sunlight to warm building in winter months, each with a corresponding reduction in energy demand. As an example, benefits from a mature 25” diameter White Oak in front of a single-family home in Elizabethton yields $215 in benefits annually (see chart at right – Casey Trees Benefit Estimator). It should also be noted that for every $1 spent maintaining a street tree, 2-5 times that investment in these benefits are realized.

(INSERT GRAPH AT RIGHT)

While $215 a year may not seem incredible, it’s the scale of the urban forest that really makes it powerful. Imagine these numbers attached to multiple trees at each residence and multiplied by the thousands of residences in Elizabethton and you can begin to realize the enormous economic benefits of our urban forest. By further extrapolating tree benefits to the Carter County scale, the numbers are astounding. From the U.S. Forest Service’s iTree Calculator, highlights include: 10 million pounds of air pollution removed every year, a 14% reduction in the number of school days missed due to air quality issues (to include asthma), a 2% reduction in number of work days lost due to health issues, the equivalent of 890 vehicle emissions removed from the atmosphere every year, nearly 30 million gallons of runoff water avoided, and nearly 30 million tons of carbon dioxide stored. Together, these benefits and others total up to over a trillion dollars in realized tree benefits for the county.

Businesses in Elizabethton also stand to gain from a sustainable urban forest. Increasing the urban forest canopy and the walkability of a downtown can be the foundational success required to get more people out and about in key business districts. Studies show that increasing canopy cover has been proven to increase the amount of time people dine and shop in downtown areas, and customers are often willing to pay more for certain goods and services if businesses are located on tree-lined streets. (Spirn, 2010). This type of success can trickle down. Increased retail business districts attract more new businesses to these districts, which helps to attract more conventional/industrial business to a region. In fact, office and industrial areas located in or near green settings are in high demand by employers – studies show that shaded areas to visit during breaks translates into more stress-free, productive employees. Workers without a view of nature from their desks reported 23% more instances of illnesses than those with a view of greenery. Additionally, healthy trees can add up to 15% to residential property value, while simultaneously reducing the frequency that streets need to be repaved by half. (southernforests.org)

SOCIAL AND HEALTH ASPECTS

One of the main reasons I find urban forests so interesting is their incredible ability to help us connect with each other and maintain a healthy lifestyle. The fact is that urban forests are the forests most humans experience every day – 55% of the world and 80% of the U.S. population live in cities.

I’ve researched the social and health implications of the urban forest for years and have found some amazing connections. For example: proximity and access to green space have been linked to better mental health. (Barton, 2010) Exercise can reduce blood pressure by 3% to 7%. Exercising in green environments may enhance this reduction. (Pretty, 2005) Exposure to green space was negatively associated with the rate of type 2 diabetes, where the strongest effect was found for neighborhoods containing 41-60% green space. (Astell-Burt, 2013) Availability of parks or greenspace was shown to mitigate feelings of depression. (Lee, 2010) The presence of trees was significantly associated with the presence of people in outdoor public spaces in an urban housing community. The mean number of people in areas with no trees was 1.32; the mean number of people in areas with trees was 4.45 – 237% higher. (Coley, 1997) Social connections were positively correlated with tree canopy. (Holtan, 2014) Urban residents who reported visiting a local park for more than 30 minutes, versus those who did not, were three times more likely to have at least four good friends in the area. (Kazmierczak, 2013) Those who reported the highest degree of neighborhood greenness were nearly twice as likely to be in the better mental health category, compared with those who perceived little greenness in their neighborhood. (Sugiyama, 2008) Greater tree canopy and higher levels of greenness near a mother’s home was correlated with reduced risk of low birth weight in newborn babies. (Grazuleviciene, 2015) For elderly citizens, the probability of survival over a five-year study period increased with availability of green space for walking, nearby parks and tree-lined streets. (Takano, 2002) Having a view of trees from a hospital window decreased surgery recovery times as well as the amount of pain medication needed. (Ulrich, 1984) Spending time in a forest has been found to increase cancer-fighting proteins and natural killer cell activity. (Li, 2007) Walking outdoors is associated with higher levels of positive feelings. Those who live in greener areas have reported higher levels of happiness. (Keniger, 2013) Several studies suggest spending time/exercising in green settings versus other environments has a positive effect on children with ADHD. (Jensen, 2006) Suffice to say that the data is in, and the correlation of urban forests and green space to healthier, happier lives is certainly there. The good news for us is that urban forests provide these benefits to us virtually free of charge! All we have to do is plan, plant, and care for them to realize these benefits for our entire community.

ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS

Environmental aspects are important to making our area a clean, thriving place for generations to come. A review of available EPA data, dated 2016, considers the Watauga “impaired,” but specific tree species and rain swales or permeable sidewalks/parking lots could potentially help improve that rating by infiltrating water and reducing the amount of polluted runoff entering our nearby Doe and Watauga Rivers. Everyone knows that trees enhance air quality, but one study in particular found that simply providing a buffer zone of 10 meters between major roadways and sidewalks reduced the lead content dramatically, adding trees in the buffer zone provided the greatest air quality benefits. Similarly, trees reduce the amount of CO2 in the air which helps contribute to an easing of the typical urban heat island effect. Aside from providing a natural beauty, trees also conserve water, reduce soil erosion, reduce noise, lower air temperature, reduce glare, reduce windspeed, and provide plant and wildlife diversity to a fragmented urban habitat.

I’d like to thank you for your interest in this article and the future of Elizabethton’s urban forest and sustainable development. If you’re asking yourself what you can do to help create an even better Betsy, here are a few ideas. First, get involved. Perhaps bring some ideas or inspiration to a city council or planning meeting, consider getting involved in the incredible new Mainstreet program, or even consider taking the lead on making Elizabethton a Tree City USA community. If none of those options sound like you, consider simply planting a tree! As the saying goes, “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago, the second best time, is now.”

(About the Author:In my high school days, I spent a lot of time being completely mediocre in a football jersey, but I was able to find some success in the competitive forestry program at EHS. Those experiences led me to UT where I got my B.S. in Environmental Science and Forestry and commissioned in the Air Force. I flew B-1 bombers for several years before changing gears and studying Urban Forestry and Natural Resources in a Master’s program at Oregon State University. I became a certified arborist, and took a job with an urban forestry consulting firm based in Colorado where I focus on making cities better through their urban forest resources. )